Lost Knowledge of the Imagination

by Floris Books • 17 April 2018 • Extract, Gary Lachman, Lost Knowledge of the Imagination, Philosophy of Human Life • 0 Comments

The explosion of science in the early 17th Century was “a new way of knowing and understanding ourselves and the world we live in”. But did this mean we ultimately forgot about the ‘other’ way of knowing? This paradigm shift is what Gary Lachman identifies as the ‘Lost Knowledge of the Imagination’.

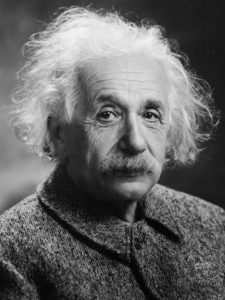

In this extract from his latest book, Lost Knowledge of the Imagination, Gary Lachman explains how famous figures such as Albert Einstein exhibit the ‘spirit of finesse’, or ‘other’ way of knowing.

A new way of knowing the world and ourselves arose in the early seventeenth century and quickly came to occupy a position of importance and authority that now, some four centuries later, seems unshakeable. To be sure, many have questioned its authority and accuracy in dealing with aspects of our experience that it seems ill-equipped to address. We have seen that even at the outset of this new way of knowing, the ‘spirit of geometry’ was advised not to forget its close cousin the ‘spirit of finesse’ and that it should not dismiss its contribution to our understanding of ourselves and the world.

The person who raised this concern, Blaise Pascal, had the credentials to do so. He was both a mathematician and logician and a soul sensitive to the deeper, more ambiguous significances of human existence. He could ponder the complexities of number theory and work out the intricacies of what later became probability theory, essential to our modern use of statistics, but he was also concerned with the meaning of human life and the ever-present imponderables that make it a mystery.

Many came after Pascal and one could write a history of modern Western consciousness from the point of view of the scores of important figures that have echoed his concern. A list would include Nobel Prize winners, celebrated writers, artists, poets and philosophers. By now it would include filmmakers. To tally it up would be tedious, but it could be done, and most readers I suspect could reel off a handful of names if pressed. Even as towering a figure as Einstein comes down on the side of the ‘other’ way of knowing.

In an interview in 1929 with The Saturday Evening Post, Einstein said: ‘I believe in intuitions and inspirations. I sometimes feel that I am right. I do not know that I am’. He said that when expeditions, financed by the Royal Academy, were sent out to South America and Africa to confirm his theory of relativity – which they did during the solar eclipse of 29 May, 1919 – he was not surprised when he was proved right. ‘I would have been surprised,’ he said, ‘if I had been proved wrong’. When the journalist George Sylvester Viereck asked Einstein if he trusted his imagination more than his knowledge, Einstein replied: ‘Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world’.

Einstein was not so forceful a prophet, but his belief in imagination as a creative power was no less than [George Bernard] Shaw’s. In Cosmic Religion he wrote that: ‘Imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research’. Einstein showed that he too had a copy of Ernst Jünger’s ‘master key’ when he remarked that: ‘At times I feel certain I am right without knowing the reason’.

As we have seen, those who follow the spirit of finesse – as Einstein is doing here – find it difficult, if not impossible, to explain how they know what they know. They cannot express it directly and can at best speak only in metaphor, analogy, or symbol. Einstein knew, but he didn’t know how he knew, or at least he wasn’t able to say how he knew, in the kind of language scientists are supposed to use when they talk about their discoveries. They are supposed to carefully lay out all the details for everyone to see, and if required, walk us through the steps. Einstein knew in the way that scientists are not supposed to know. He knew in our ‘other’ way of knowing.

About Lost Knowledge of the Imagination

Lost Knowledge of the Imagination is the latest fascinating work from Gary Lachman. This insightful book argues that we must reclaim the ability to imagine and redress the balance of influence between imagination and science.

is the latest fascinating work from Gary Lachman. This insightful book argues that we must reclaim the ability to imagine and redress the balance of influence between imagination and science.

Floris Books publish a range of books from Gary Lachman. They include Caretakers of the Cosmos, The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus and a biography of Rudolf Steiner.