The Computer that Measured the Universe

by Floris Books • 7 May 2021 • Astronomy, Stargazing • 0 Comments

Discover the work of Henrietta Swan Leavitt in the feature article from Stargazers’ Almanac 2021

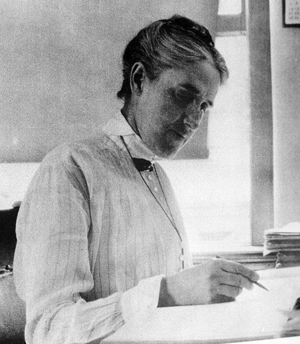

The year 2021 marks the centenary of the death of one of the lesser-known but very significant heroes of early twentieth-century astronomy, Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868–1921). As we gaze into the night sky, we can say with a degree of confidence how far away are some of the distant objects we see through telescopes. For example, the Andromeda Galaxy is known to be some 2.5 million light years away. An affordable telescope can show us the remote quasar 3C273, blazing more than 2,000,000,000 light years from us.

Leavitt was one of a group of women employed in the 1920s at the Harvard Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts as ‘computers’, an early use of the word. The computers’ task was to scrutinise the large black and white photographic plates taken by the Harvard telescopes and others, measuring and cataloguing the brightness of stars, and noting any patterns they might discern in the stars’ behaviour. It was known in the 1920s, and had been for millennia, that some stars change their brightness over time.

For example, in the constellation of Perseus, Algol, the famous Demon Star of the Arab astronomers of old, is seen to change its brightness over a period of just under three days. The name Algol is derived from the Arabic ‘Al Gul’, the Ghoul or Demon. The star’s sinister behaviour later caused it to become the baleful eye of Medusa in the Greek legend of Andromeda, saved from the clutches of a sea monster by Perseus using Medusa’s severed head to petrify the creature – literally.

In early 1904, Leavitt was poring over a series of photographic plates sent to Harvard from the Arequipa Observatory in Peru. They showed images of the Small Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way 180,000 light years away and about 7000 light years in diameter. She found to her surprise that several of the individual stars visible amid the general misty cloud of background stars were varying in their brightness, and wrote a report in 1908 describing the behaviour of 1777 Variables in both the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds. In her own words, ‘It is worthy of notice that the brighter variables have the longer periods.’

After a period of illness she returned to her work, discovering more such variable stars. They are now known as Cepheid variables, after a bright example of the type, Delta Cephei in the constellation of Cepheus, 887 light years away in our own Milky Way, first described in 1784 by John Goodricke, observing from York.

How do Cepheids help us to measure distances of other galaxies? The period-luminosity (brightness) relationship of these stars means that we can work out the intrinsic brightness of a Cepheid from its period of variation and then compare it with its apparent brightness seen at a great distance, giving us information about how far away it lies. It is what is rather curiously known in astronomy as a ‘standard candle’, a light that gives information about its own distance.

The method works as long as individual stars can be discerned, so for very remote objects like 3C273 other techniques have been devised. As estimates have been refined over the decades and satellites like Hipparcos are providing ever more accurate measurements of what shines at great distances from us, remember that the next time you wonder at the sight of the Andromeda Galaxy and contemplate the fact that its light left it when the height of human technology was a stick and a rock, it was Henrietta Swan Leavitt whose work handed us a ruler to measure the nearby universe.

This large-format almanac allows you to step outside and track the planets, locate the Milky Way, recognise the constellations of the zodiac and watch meteor showers.

It’s designed specifically for naked-eye astronomy — no telescope required! — making it ideal for beginners, children and backyard astronomers. It is a perennially popular Christmas gift — and one which lasts the whole year round.